You’ve just rolled up your umpteenth human fighter or Dragonborn fey-pact warlock and you’ve gotten to the point where you pick your languages. Your GM didn’t tell you ahead of time which, if any, would be useful for the adventure, so you picked some that seemed appropriate for the character. Maybe Celestial (they teach Enochian in schools, right?) and Elven. And then they never come up. It turns out that, just like in the movies, more or less everyone in the world speaks the same language. Where did things go wrong — and is there still a place for these languages to matter?

History: Languages of D&D

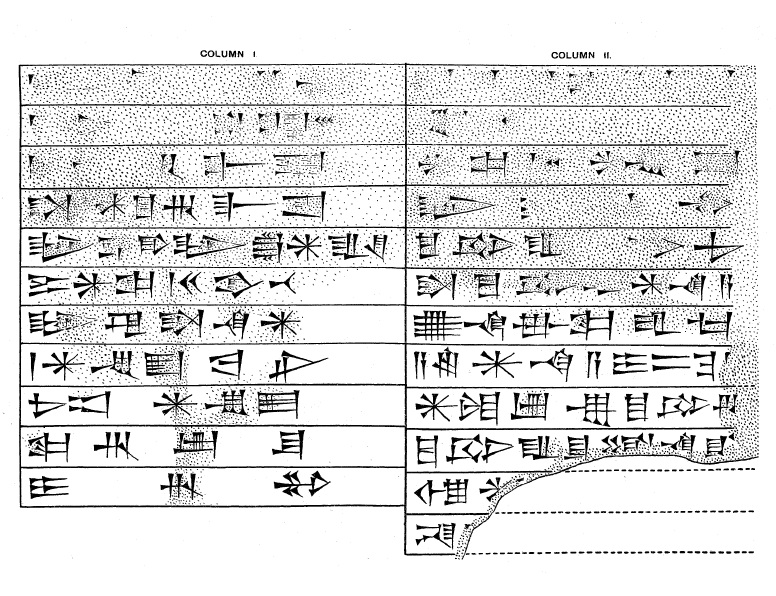

D&D didn’t always use its current canonical languages: Common, Elf, Dwarf, Orc, Sylvan, Primordial, Celestial, Infernal, and Abyssal, with a few miscellaneous ones for other player and monster races. The fact that Druids still have a secret language of their own rather than speaking Sylvan is a holdover from those dark times.

If we rewind the clock all the way to first edition Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, you’ll notice a couple of things that probably seem a bit silly to many modern D&D players. One: every individual monster type has its own language. Fire giants, frost giants, and hill giants all speak their own languages as do hobgoblins, goblins, and orcs. There wasn’t a generic Giantish or Orcish, and even generic Elvish didn’t apply to all kinds of elves.

Two: characters spoke the secret language of their character alignment. This is something that is, to most people, self-evidentially silly and comes from a fusion of ideas from the Elric of Melnibone series, the Poul Anderson novel, Three Hearts and Three Lions, and a gamist desire to differentiate the good guys and bad guys. As silly as it is, however, it somewhat survives in Celestial, Infernal, and Abyssal.

The languages consolidated over time. 2e dropped alignment languages, 3e merged all the dialects of giant and fairy and some others, and 4e combined all the elemental languages. 5th edition, which started out as the nostalgia edition, was too afraid of rocking the boat to introduce any changes.

Theory: Language and Culture

There’s a spectrum, then: on one end there is one language (sometimes more) per culture, and on the other end there is one language (sometimes less) per species. Within the context of a generic fantasy world, which of these sounds more plausible, and which one is better for a game?

On the first count you’d think option one is the obvious answer. Of course, that may not be universally the case — it all depends on your assumptions about the world. Take the elves, for example. The classic elf cultural divide in D&D-derived fantasy is between the Wood Elves (say, Dragonlance‘s Sylvanesti) and the High Elves (say, Dragonlance‘s Qualinesti). 5e’s upper limit for Elven lifespan, barring weird magic, is somewhere around 750 years. If your generic fantasy world is about 6,000 years old, that means it’s only been 7 Elven lifetimes (rounding down) since the creation of the world.

On the other hand, if we assume humans live on average for about 80 years, then it’s been about six of our lifetimes since the beginning of European colonization in America. There’s been a fair bit of linguistic change for us in that time, but it’s worth examining if that would necessarily be the case for elves. English had just emerged from centuries of turmoil. And, while other languages were more conservative in their history, the average English speaker still has less difficulty with Chaucer’s straightforward but more archaic English, than they do with Shakespeare’s more modern, endless collection of poetry.

And that’s humans, in the real world. Elves, on the other hand, have usually been entirely too into themselves and their past ever since Tolkien effectively created them. And it gets worse if we use older assumptions about elf lifespan: in 2e they averaged out at about 2,000 or so, and in Tolkien the only thing that kills them is violence or sadness. There simply might not have been enough time for the elves to form a large number of distinct languages and cultures.

It is possible that your generic fantasy world is a fair bit older than 6,000 years — say, somewhere on the order of 3.4 billion and older, and previously populated by flying polyps and serpentine civilizations. In that case, the question is how long have the elves been on your miserable rock? The answer, probably, isn’t much longer than 10,000 years, and thus the point still stands.

Game: It’s All About Feeling

But that’s just the elves. Dwarves are probably even more conservative, but they live for only half as long. And what about the hobbits, gnomes, orcs and whatever other fantasy folk populating the far corners of D&D lands? At some point, that argument just falls apart.

Fortunately, as far as actual play is concerned, it doesn’t matter how many languages are in the game. All that matters is what your character can understand.

Let’s say your party has just hit mid-level. They’re stretching their legs and leaving the cliched D&D starter valley and going anywhere else. The winds of adventure take them to the globe’s four corners and they eventually walk into a town which language they don’t speak.

You do a couple of funny scenes where everyone misunderstands them, but eventually everyone gets sick of it. At that point the GM lets them come across an urchin or a peddler, or somebody that speaks their language, the party hires them as an interpreter, and suddenly the language barrier doesn’t matter anymore. Everyone forgets that it, and the interpreter, even exist, until someone decides to make a thing out of it again. No harm, no foul, and no real impact on playability.

Consequently, the number and kinds of languages you use in the game only impact the feeling you want to evoke. Do you want a pick-up-and-play anything-goes romp? Common will likely be the only thing people speak; other languages will only exist when they’re written on tomb doors or on strange parchment torn from a dying man’s glove. Conversely, if you want a more grounded game centered around politics, travel, or demon-hunting, it might have little superstitious villages that speak their own insular language hiding behind every hill. In that case, the party travels — but the people don’t.